How Energy Storage’s Growth Trajectory Differs From the Early Days of Solar

December 04, 2019

DENVER — It’s become a cliche to compare today’s energy storage market to where the solar industry was a certain number of years ago. But storage’s trajectory differs from the early growth dynamics of solar power in a crucial respect: It transcends the geographic boundaries, dictated by sunshine and policy, that constrained solar’s rise.

Fast-acting battery technology performs many roles: frequency regulation, capacity, deferral of wires upgrades, resilience, firming renewable generation and more. It does not rely on a geographically specific weather pattern or any one set of state policies to become valuable, and it’s already asserting itself across the U.S., said Daniel Finn-Foley, energy storage director at Wood Mackenzie, speaking Tuesday at GTM’s Energy Storage Summit in Denver.

Solar reached the big time early in California, thanks to abundant sunshine and supportive state incentives. Pockets of development later formed in Hawaii and the Desert Southwest, and in the less sunny but politically supportive New England states. But it did not spread evenly, and whole regions such as the Southeast and Midwest trailed behind for years.

“Energy storage’s value lends itself to a much more diverse range of geographies,” Finn-Foley said in an interview after the talk. “It’s finding value in wholesale markets; it’s finding value in vertically integrated utility markets; it’s finding value for residential deployments — really, just about everywhere.”

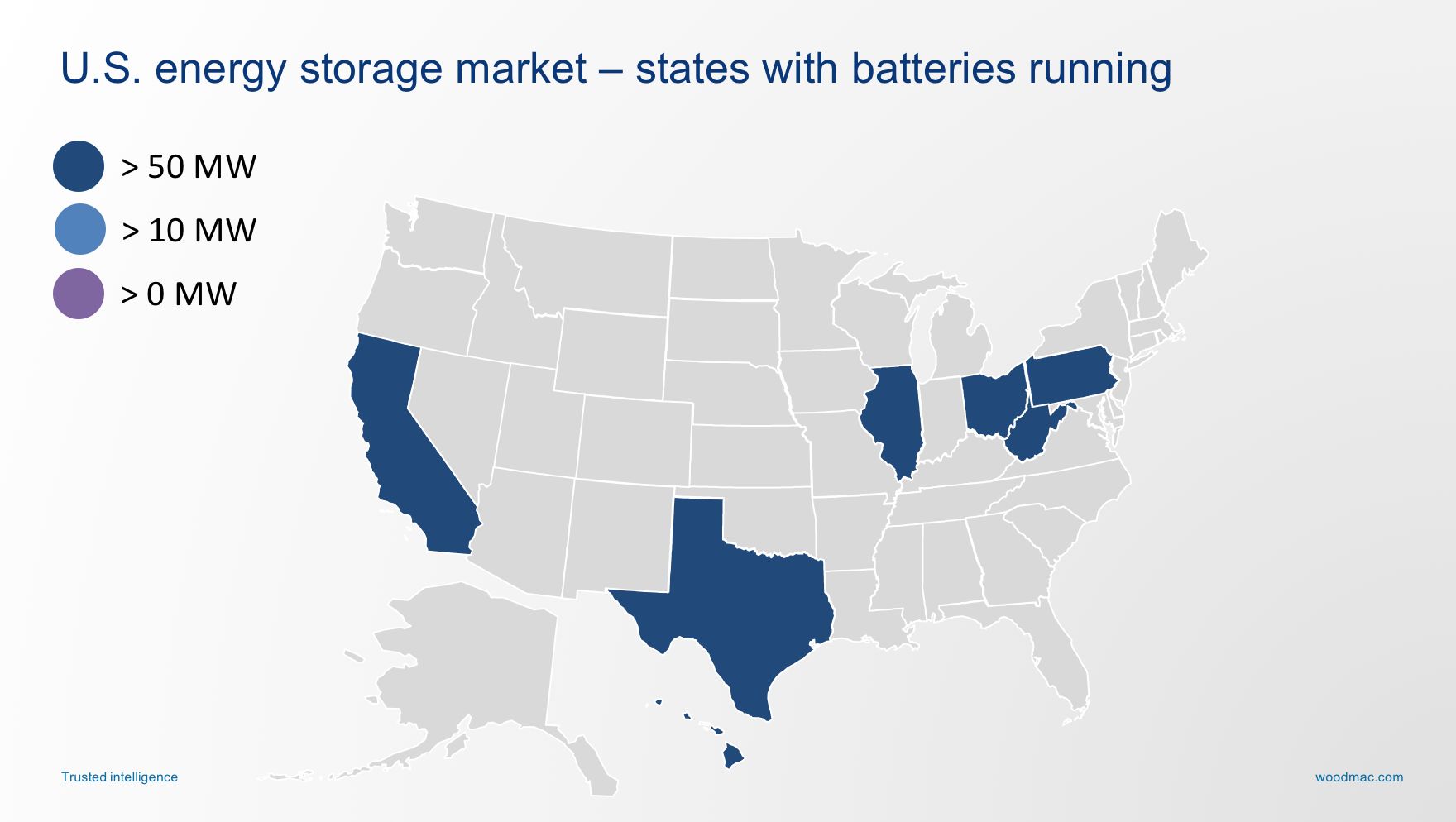

Storage is still considered new and experimental in many states, but a map of where development has taken place reveals its border-crossing appeal. Here are the states that already operate more than 50 megawatts of battery grid storage, according to Finn-Foley’s presentation.

The blue cluster of states to the east reflects the first commercial storage market, serving a fast frequency regulation market in the PJM grid. That market burned brightly for several years but dimmed when rule changes made the service less valuable.

On the opposite coast, California approached storage through a top-down procurement mandate that spurred utilities to acquire grid batteries. But these tools proved unexpectedly useful when the Aliso Canyon natural-gas leak jeopardized fuel supplies for Southern California power plants. The state fast-tracked storage procurement to install emissions-free capacity in urban areas in just a few months, something traditional power plants couldn’t possibly achieve.

Hawaii hit on storage because solar installations were flooding its isolated island grids: Batteries offered a way to store that power for the evening peaks when it was more useful. Hawaii also faces unusually high fuel costs because fossil fuels must be shipped there; solar-plus-storage beat incumbent power sooner there than on the mainland. And the state’s early commitment to a 100 percent renewable grid made storage all the more necessary.

Rounding out the map is Texas, largely covered by the competitive energy-only ERCOT market. No state incentives help storage there; indeed, its classification as a generation asset effectively bars distribution utilities from using batteries to assist their wires infrastructure. But developers have found business cases worth investing in, such as saving clipped solar power, arbitraging wind power and hitting peaks in the energy market.

Storage developers did not need to replicate the same conditions in each of these early markets. They found different routes to make themselves useful based on the varied capabilities of storage itself.

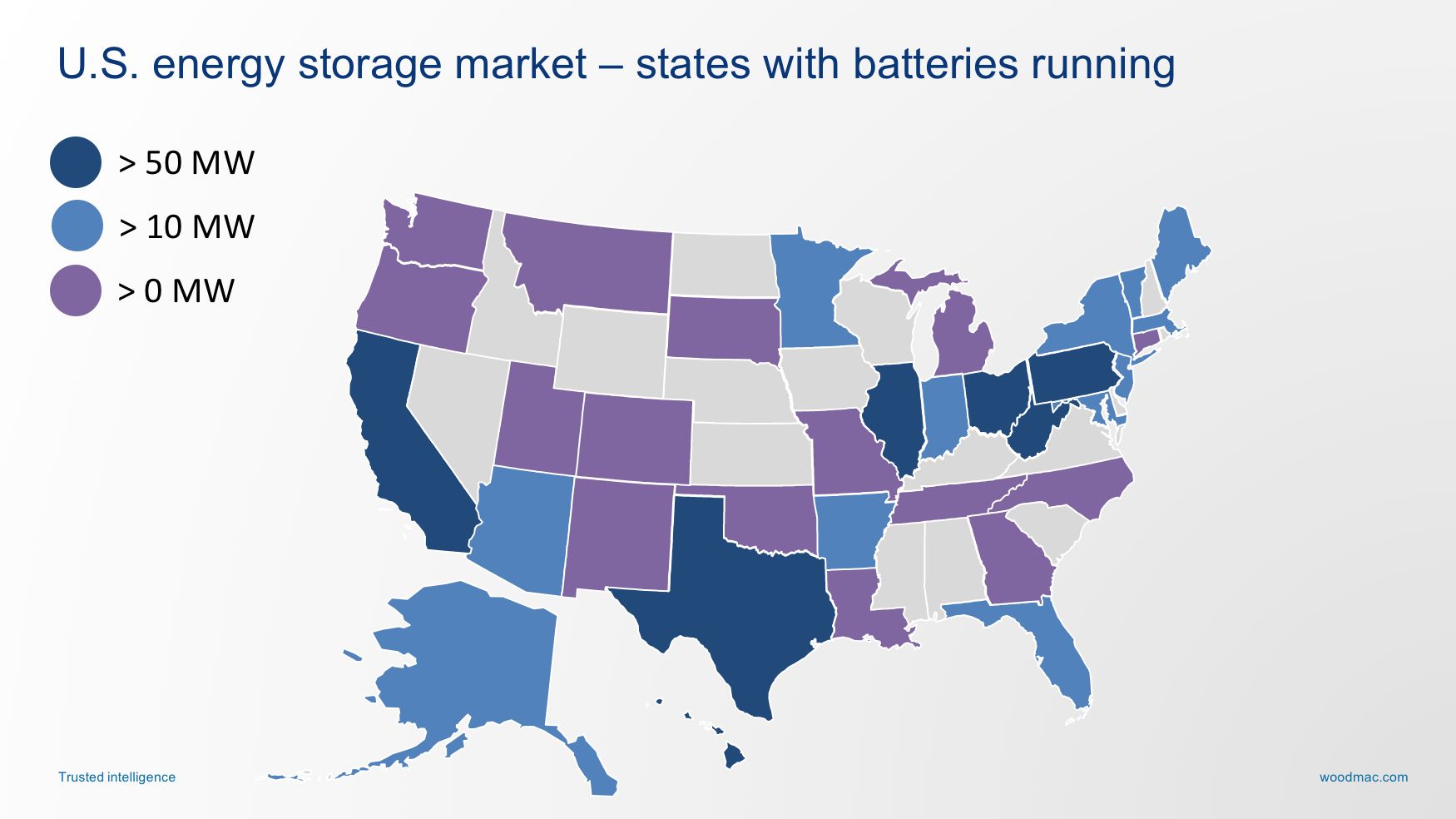

Layering in states that have more than 10 megawatts operating and more than zero reveals that states without any advanced energy storage are clearly in the minority.

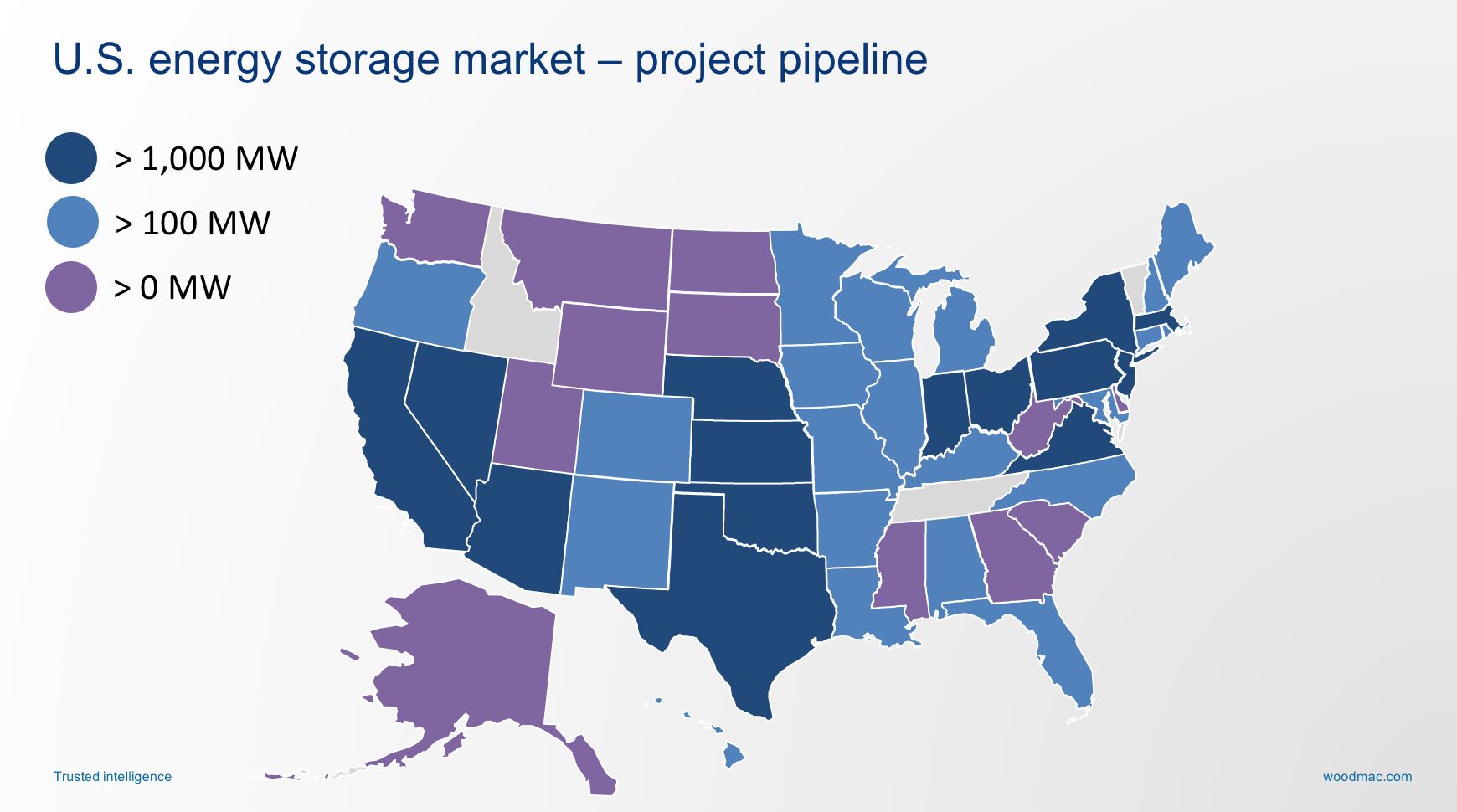

And looking ahead at states’ contracted pipelines depicts an even more complete takeover.

This geographic diversity matters for predicting the growth prospects of battery storage, which is hard to do because the historical record offers little insight into future deployments.

Conventional estimates woefully under-predicted the rise of solar over the last decade. Finn-Foley displayed the Energy Information Administration’s projections for national solar deployment from 2011, 2012 and 2013. Even after two revisions upward, the expected cumulative installations for 2019 ended up equaling the utility-scale solar installed in North Carolina alone, a far cry from predicting solar for the whole country.

The experience watching solar evolve and repeatedly defy expectations should inform modeling for the ramp-up of energy storage years later. But Finn-Foley’s argument cautions against extrapolating too much from the solar experience to the storage experience, because storage can follow a more diverse array of paths to market.

The hard work put in by the wind and solar industries to load up grids with cheap renewable power will eventually serve to boost interest in storage too.

“When you have these long renewable grids, it’s no longer the industry pushing upward and saying, ‘Here’s what we’re capable of,'” Finn-Foley noted. “It’s now policymakers and regulators pulling upward and saying, ‘Storage, we need you.”

Put another way, Finn-Foley said, “The wind energy and solar energy industries are writing checks that energy storage is going to cash.”

Source:How Energy Storage’s Growth Trajectory Differs From the Early Days of Solar